AN INTERVIEW WITH STUART CLARFIELD

CREATOR OF “KENSINGTON MARKET: HEART OF THE CITY”

Tues. Nov. 4, 2025, Bar Centrale, 1095 Yonge St., Toronto, 10:30am–12:30pm

Neighbourhoods change. Sometimes they age, sometimes they expire. But they never stay the same. The neighbourhood where you grew up, learned to ride a bicycle and made friends-for-life isn’t that neighbourhood anymore. The houses might be more-or-less the same, but no neighbourhood has ever been about buildings. A neighbourhood is about time and place, gathering spaces, and mostly about people. This is the premise of Stuart Clarfield’s documentary Kensington Market: Heart of the City, a film about a Toronto neighbourhood.

For Stuart, a neighbourhood is about “vibe”—feeling and character, and more than anything, about human behaviour. What Kensington Market seeks to tell us is how a small neighbourhood in the heart of North America’s third largest city has managed to maintain its neighbourhood-ness for more than 100 years. Can it keep going? If so, in what form? What elements of Kensington’s rare personality can we hope to hang on to?

It’s a recurrent phenomenon everywhere in the world, in developed and developing countries alike: neighbourhoods evolve, and it’s mostly a healthy thing. Populations, planning regulations, economic pressures, political priorities are all in constant flux, and neighbourhoods need to keep pace. They’re only a product of their peculiar circumstances, and circumstances don’t remain constant.

There is always a desire to preserve a neighbourhood, because of what it represents—certainly to its residents, but often to non-residents as well. And if a neighbourhood somehow contributes to the larger urban population, why shouldn’t it be preserved in some way? The question is: In what way? What exactly are those elements that constitute the neighbourhood, and amid necessary renovation and reconstruction, what must be preserved for the essence of the neighbourhood to survive? How do we decide what’s worth clinging to and what isn’t? Is it all just nostalgia, or is there something more pragmatic? What makes a neighbourhood special and something that we should preserve and protect?

That is, before it’s too late. As Joni Mitchell has pointed out, whether it’s paving paradise or nuking neighbourhoods, oftentimes, “You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.”

"A city of neighbourhoods" is the nickname for Toronto, Canada, because it is made up of numerous distinct communities, each with its own unique character, history, and local businesses. The city's growth has resulted in a diverse collection of neighbourhoods, and this nickname reflects the strength and vitality of these individual areas. – Google AI summation: “A city of neighbourhoods.” 20 Nov. 2025

“Strength and vitality.” Toronto has seen its share of vanished neighbourhoods. Remember Yorkville Village, once a musician’s haven, now a high-end outdoor shopping mall? And what about Mirvish Village and Honest Ed’s (“A Bargain Centre Like This Happens Once in a Lifetime” ¹ )—soon to become an exclusive enclave of multistorey rental apartments. At the same time, we’ve succeeded in saving a few neighbourhoods. The Annex was nearly bulldozed to make way for an expressway. The (Lower) Beaches is still a viable neighbourhood thanks to continuous community involvement.

Kensington Market is a Toronto neighbourhood that is unique in many ways and, partly as a result, has somehow managed to survive as an identifiable precinct that has a value to the whole city. Its loss or partial erasure would be a civic tragedy. Kensington’s uniqueness is not at all about its architectural heritage, or its role as the scene of historic events, or as the birthplace of famous people. In fact, the opposite is true. It’s about commonplace activities and ordinary people—immigrants from every imaginable corner of the world—building and maintaining an ad hoc community that was, and continues to be, welcoming to all.

But Kensington’s days may be numbered.

The film Kensington Market: Heart of the City is an homage, but it may also be a requiem to a precious Toronto neighbourhood which, like urban neighbourhoods everywhere, is under increasing pressure to surrender to high-rise developers. The film presents us with impressions of the neighbourhood: what it represents historically, what it offers culturally, and what its demise will mean not just to its residents and the city, but to the idea of neighbourliness everywhere.

I had the opportunity to sit down with the film’s creator Stuart Clarfield to discuss his ideas about the film, about Kensington Market, and about neighbourhoods in general. Our two-hour conversation was wide-ranging and tended to wander from topic to topic. Stuart likes talking about his film and what he has learned from it. His contribution to the discussion was a lot like the film: well informed, well considered and passionate. And, as it turns out, Stuart and I have similar ideas about neighbourhoods. Stuart’s views are those of a film maker, and mine are those of an architect, but we both have an affection for Toronto, the city in which we were born, and we both care about preserving its unique character through its neighbourhoods.

If I were to succumb to the temptation of comparing the film to a work of architecture, I would say it is artfully constructed, sensitively detailed, visually engaging, and has a surprising sense of form and space.

To view the trailer, and for information on upcoming streaming events and VOD, visit the film site.

•••••

What follows are edited excerpts from my conversation with Stuart Clarfield. I’ve reorganized the dialogue into specific topics, although some elements tend to bleed from one topic to another.

PART I: THE KENSINGTON VIBE

THE OBJECTIVE OF THE FILM

THE RIGHT ANGLE JOURNAL: I wondered what got Stuart interested in the subject in the first place, and what he hoped the film might accomplish.

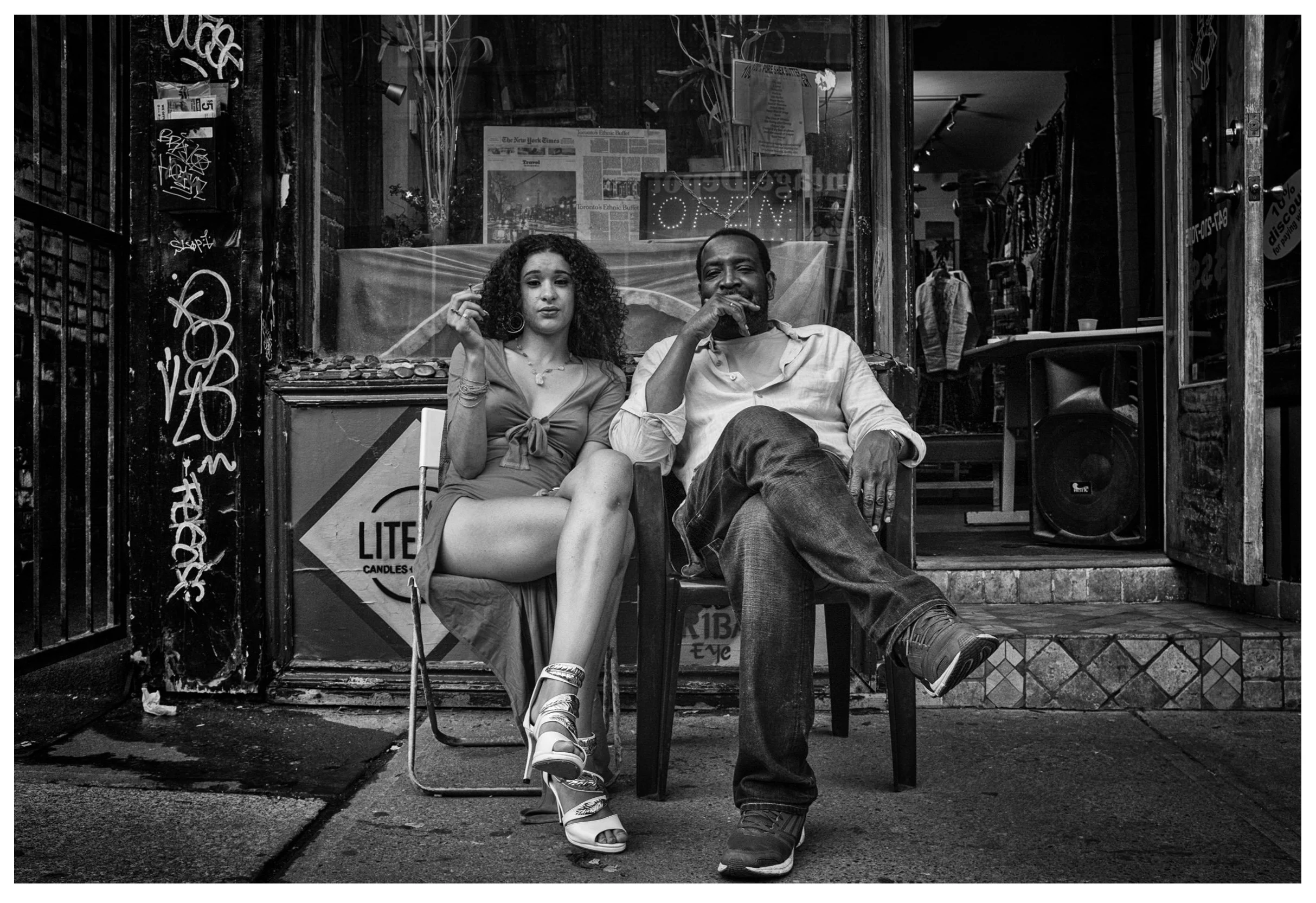

STUART CLARFIELD: Originally, the project was to try to capture Kensington’s history. And, of course, every time you point the camera in Kensington, it’s an art canvas. The texture—the place and the people—is always incredible. I wanted to use the present as a door into the past. But then, when we started to see the impact of gentrification and development on the neighbourhood, we started to follow that, and it became half the film. But that was not the intention.

Then, as we continued working on the film, it became very clear that you could remove the word “Kensington,” and drop the word “Toronto” into anything we’re saying because it’s just mirroring what’s going on in the city.

CREATING THE FILM: A STORY IN ITSELF

TRAJ: So, would you say that your original intent was to educate the public as well as entertaining them? In fact, how did it all get started?

SC: The first thing that happened was that I got a call from TMU’s ² RTA Media department—the person who ran the documentary course knows me. She said to me, “Do you want any interns for the winter semester?”

I said, “I don’t have anything for them to do.”

And she said, “I’ve got a bunch of students who really want to work on a documentary, and you do documentaries, so couldn’t you take on a few of them?”

I said, “I don’t have a project, but let me get back to you.”

So, I thought about it. I’d wanted to do something on Kensington for a long time, because I have a family connection to it through my great grandparents on one side and my grandparents on the other. They both emigrated from Europe and lived in Kensington. My parents were both born there, before they moved to the suburbs, where I was born. I didn’t really “find” Kensington until I was about 15 years old and saw all the vintage stores and the art and I fell in love with it. Since then, I’ve stayed connected to it.

Around 2005, I was working with a theatre company that was resident at St. Stephen-in-the-Fields [the Anglican church on College Street that is part of the Kensington neighbourhood], when it was handed an eviction notice by the Anglican archdiocese which wanted to sell the church for condo development. I became part of a group called The Friends of St. Stephen’s that wanted to keep the congregation in place and protested against the notice. Somehow, we succeeded.

Then 10 or 15 years later, I got this offer of interns. So, I asked the folks at St. Stephen’s if we could have a little office for a few months, where the interns could work while they got to know the neighbourhood and do some research. Maybe I could get a bit of crowd funding and start shooting. My intention, at this point, was just to get a sense of the history of the place, and then we could start interviewing people who were pulling up stakes and leaving. There are so many cases where families have been there for many, many decades, and now we’re losing them. There were a couple of Portuguese stores near the park that had been there for 40 or 50 years, and I thought that would be a good place to start.

Then, Maggie Helwig [the priest At St. Stephen’s], told me about an upcoming public meeting being held by the developers of a new condo development. So, I said OK, and we filmed it. Then, a couple of weeks later, she mentioned that there would be a meeting of all the tenants who were being renovicted or having their rents doubled or tripled. The meeting was to discuss available legal resources and to let them know what their rights were. So, we went to that meeting too.

That’s how the Kensington film got started. There was no broadcaster that came on board. There was no arts council that supported it. It was DIY.

The whole idea was to get enough material to make the film . . . and to find an appropriate ending. You can shoot a documentary film endlessly—no one tells you when you’re done—and we hadn’t chosen a particular subject, with a beginning, a middle and an end. We just started filming the neighbourhood. So, it went on for quite some time until, finally, the end of the arc became obvious: We could show the colour of the present and the past, and we would show very clearly where we’re headed.

Actually, on the last shoot day, I was walking past a corner restaurant at sunset. Some workers were hauling out all the tables and chairs and throwing them onto the back of a dump truck parked on the sidewalk. I got out my iPhone and started shooting because I thought, “This is the end of the film: people moving out of the neighbourhood because they can’t afford to stay.”

That stuck in the film for a long time, but it got cut out during editing. We also had a whole sequence on the King of Kensington³ that also got cut out. And there was a whole thing on the art market—on the hippies taking over from the beatniks, and then the punks—all of my favourite stuff —things that I could most relate to—all of it got lifted out of the film at the end. It’s still on YouTube and on the DVD, but for the sake of the narrative, I had to take it out so that people wouldn’t think, halfway through, that this was only a history film, and lose interest.

As a film editor, I had to make tough decisions about what would remain, but there were two or three things that I had to keep in because they were very important to me. At the end, there is the poet on the street. To me, that poet is the spirit of the market, the soul. Then, near the end, there’s the Brazilian drum crew marching on the street—similar to the street march sequence that starts the film. That winter solstice parade used to happen every year on the evening of December 21st, but COVID stopped it for a while, and then the destination that they used to go to became a condominium. So things continue to change.⁴

In the procession, there are about 10,000 people —a river of people—flowing through the streets. I love that as a metaphor. First, because there’s been a river of humanity coming through that market, for 160 years, and this was a sort of visual representation of that. Second, because it was about all these people moving freely and managing to feel comfortable walking through the streets. So that march of people at the beginning and end acted as bookends.

THE HEART OF THE CITY: ACCEPTANCE, COMMUNITY, & A LITTLE HISTORY

TRAJ: Toronto is advertised as “a city of neighbourhoods,” which suggests a lot of distinct little communities with a spirit of friendliness and camaraderie. But we seem to live in a world that doesn’t have much space for camaraderie. On the other hand, if we look, for example, at the 2025 World Series,⁵ where the whole takeaway is not about who won, but about the kind of team spirit that was generated, there’s a glimmer of hope. Team spirit— sense of community—feels like a major theme in your film.

SC: This neighbourhood got established because it accepted the marginal communities that weren’t welcome anywhere else. People just knew that there was a neighbourhood that was non-judgmental and accepting, and they gravitated to it.

The foundation for this neighbourhood character was a group of people who immigrated to Toronto from Eastern Europe, didn’t speak English, didn’t dress like the locals, didn’t have the same religious practice, and felt like aliens in the city. They knew that they weren’t welcome in the general population, so they eventually ended up in this little residential area, and to survive and to keep their community alive, they turned it into a little village.

The funny thing is that the neighbourhood was originally built in the early 1800s by small builders to just have single family dwellings. It wasn’t a mass development or a subdivision, like we have now. It was just a few parcels. Eventually a lot of those middle-class families decided to move out into the suburbs and started renting to European families that had very little money. So, four families might share a one-family house. Then, when those new residents started selling on the front lawns and opening up their living rooms to conduct business, the remaining original owners ran for the hills. In short order, that new group, functioning as a community, started buying the properties and eventually, they sold or rented to the next wave of immigrants, who rented to the next wave, to the next wave, to the next wave, etc., and we ended up with what’s really a big public space —not by design, but because people felt welcome there. It’s a bizarre little case study.

A transition came after WWII, when two things happened. First, it had been a Jewish neighbourhood—it was called “The Jew Neighbourhood” and “The Jew Market,” not “The Jewish Market”—but so many young Jewish men volunteered to fight in WWII that it marked the beginning of the community’s true immersion into the Canadian population. After that, there was a lower barrier for things like university acceptance and government jobs, so an easier immersion into the city and wider society was now possible. The second thing is that there were half a million European immigrants who came to Canada in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, and Toronto was being rebuilt as a city that accepted immigrants. That’s the city I was born into and raised in. My neighbourhood was a mix of different families and almost all of them were first generation immigrants. We were all visitors who had to find our way. Newcomers felt welcome and comfortable in Kensington Market.

There’s a good illustration of this that comes out in the film. Ossie, the proprietor of Casa Coffee and part of the Portuguese immigrant contingent describes how the Jewish community welcomed newcomers and told them not to be afraid or ashamed. They were welcome in the neighbourhood. A lot of other residents confirmed this fact and added that if you were one of the new store owners and you weren’t making your rent, they would cut you some slack and give you time to get established. These were individual decisions, but they established a precedent—a role model. So, you had a bunch of people acting like a community. And the freaky part of the Kensington community is that the vibe has been passed from culture to culture, generation to generation, and kids who might feel ostracized, or not comfortable in other parts of the city, or new immigrants, walk through Kensington and sense that it’s the antithesis of a blank canvas, but it’s not a black-and-white canvas either. It’s so multi-coloured that there’s space for everyone’s vibe.

So, to me, it’s a neighbourhood that was set up to be welcoming to people, and that vibe still seems to exist, generally, in this city. But as gentrification takes hold and prices go up everywhere, there’s a new bar for being in the city: Can you afford to be here?

For decades, including most of my life, there were poorer neighbourhoods, there were immigrant neighbourhoods and there were derelict neighbourhoods, which meant there were places for people with next to no money, or people who weren’t immersed in the culture or the economy yet. There were places for everyone in this city.

One of the things I like about the Kensington neighbourhood now is that a similar spirit is still there. Folks just set up their six-foot tables on the sidewalk, paying no rent, and run their little craft enterprise in front of vacant stores asking 20 grand a month. In other cases, those stores are divided into 15 little shops, with everybody paying $1500 a month. It’s just like the original neighbourhood: people going back to their roots, knowing that if you have nothing, you’ll find a way.

There are a lot of people who don’t know the history Kensington, 100 years ago or 200 years ago. They’re young kids, or they’re recent arrivals, and they just enjoy the vibe of Kensington. What I wanted to know secretly was: Why is there a magic vibe in the air? Where did it come from and why does it transmit? I’m hoping that the film explains that a little.

THE MAGIC VIBE OF THE NEIGHBOURHOOD

TRAJ: The word “magic” comes up a lot in the film, and it’s an idea that seems appropriate to the neighbourhood, but like you, I’m curious about where the idea came from.

SC: A lot of the film is really just me capturing other people’s stories, their feelings and their perspectives. I added texture, pacing and music, and my edits create commentary. The “magic” is what people feel, and it’s very difficult to convey to a film audience. Standing in the middle of Kensington for 30 seconds will communicate far more about the magic and the vibe of the neighbourhood than an hour and 40 minutes of watching the film in two dimensions.

I think the magic is that people magically gravitate to this place and feel the sense of belonging and freedom and acceptance, and the encouragement to be exactly who they are in a world where there’s pressure to conform. The real magic is being free, among people who feel the same freedom. That is a pretty magical thing in this world.

PART II: POLITICS, PLANNING & ARCHITECTURE

CITY HALL & DEVELOPERS

TRAJ: Why don’t politicians and developers seem to be tuned into the neighbourhood issue, and to Kensington in particular?

SC: I’m a civilian and a film maker and I didn’t originally know anything about the ins and outs of any of this. I was just a witness to it and a student of how it works. Before making this film, I’d never talked to a city councillor and never gone to a planning meeting. I really didn’t understand how it all works.

From the outside looking in, my observation—and it’s in the film to some degree—is that city councillors work incredibly hard, but their portfolio is too large for any human being to manage. The number of development applications that they have to shepherd through some sort of public meeting process is staggering, and then the city planning department has its own framework, making its own decisions and interacting with applications independently. And then, in the end, the city councillor gets squished between the public and the community, and the city planning and the application, and tries to find peace. Then, whatever that peace is, it gets pushed through city council, and things move on.⁶ So, it’s pretty rare for a city councillor to say to a developer, “You’ve got a 40-story application, but we’re only going to give you five.”

A city councillor might have 20 applications or 40 or 60, in their ward and they can’t stay on top of everything. The best they can do is maybe facilitate a public process where people get a chance to hear the plan and give some feedback, but whether they can negotiate the developer down, or whether that developer is sensitive to their needs, is a case-by-case thing.

KENSINGTON BUILT FORMS: ARCHITECTS & PLANNERS

TRAJ: How are architecture and planning involved in Kensington’s success?

SC: Built forms and spaces that help bring folks into contact with one another is a huge part of what the city is, and we all want to retain that, just like other big cities do. As a civilian and an observer, I see two or three things where Kensington’s built form has created the canvas for its society and culture. The first thing is that it’s a residential neighbourhood of two- and three-storey buildings where people can be on the second or third floor and can shout down or have a conversation with people on the sidewalk. The second thing is that it’s human-scale mixed-use—residential buildings that have commercial space, so when people walk into a store, they recognize, maybe subconsciously, that they’re in someone’s home. Even newer commercial buildings are low-rise with a residential feel. The third thing is that almost all the streets are one-way and very narrow, which means that you don’t have to look two ways for traffic, and almost always, there’s no traffic at all. So you can cross the street, or see what’s going on across the street. It’s all within reach.

It adds up to the impression that people come first, not vehicles. And I think it becomes a “people neighbourhood” because there are so many people in the neighbourhood. That sounds redundant, but the scale of the neighbourhood—streets and buildings—slow the traffic down, without the need for speed bumps or a lot of stop signs. ⁷ People can congregate and move freely.

FRIENDLY ADVICE TO ARCHITECTS FROM A FILMMAKER’S PERSPECTIVE

TRAJ: What would you say to architects about how they might participate in whatever needs to be done to preserve Kensington’s sense of neighbourhood?

SC: I would say to architects that if their intention is to create or preserve an area that’s going to be conducive to human contact, there are three basics: low-rise human scale, mixed residential commercial, and if you’re building a new neighbourhood, make the streets very narrow and send the message that it’s not for cars only. The mix is really important. If they made Kensington into a pedestrians-only neighbourhood, it would soon turn into something else, which is not a living, working neighbourhood. It would just be a commercial neighbourhood.

So that’s my fourth bit of advice: Sometimes accidental is better than intentional. Kensington was built by accident, by the organic activity of humans. There needs to be some blank space for people to improvise. Don’t over-plan it. By leaving the roadways intact, you allow people to move in and out and have a normal life, and businesses can get deliveries. It looks and feels like a real neighbourhood. Also, by leaving some green space, like the Denison Square Park, it allows people to play or listen to music or just hang around. The breathing space of non-planning is important for planners.

TRAJ: Planners offer helpful directions, although they can’t always be sensitive to the needs of specific neighbourhoods. But, planning aside, one thing that all architects are aware of—the general public possibly less so—is the architect’s obligation “to protect the public interest,” as per the Architects Act. Architecture’s not only about buildings. it’s also about people—and not just the ones who are hiring you. With Kensington in mind, how can architects help?

SC: Here’s the conundrum for the architect, as I see it. In theory, you’re building structures for human use, but your clients are capitalists. So, you’re serving the interests of capital, in order to build an economically profitable enterprise, and yet, to be successful, the project has to be a place that people will use because it’s the use of that space that makes it viable. It can be a tricky equation.

It would be good if Toronto would consider protecting the human scale, and the built forms in certain urban districts and zones the way that other large world cities have done. What’s important about the city is its people and people’s relationship with each other, which, referring again to the World Series narrative, the Blue Jays perfectly represented.

TRAJ: In the beginning, architects were not involved in Kensington. it was just builders. Architects arrived only lately on the scene, so Kensington Market seems to be an object lesson.

SC: Right. A lot of people built without plans or approval. They just did it.

TRAJ: How are things changing?

SC: From an outsider’s point of view, architecture is the craft of applying ideas to how a property might be used, and serving your clients in doing so. There’s architecture going on in Kensington every day. There’s stuff being renovated, or being changed. There’s a massive development plan for the whole east side of Kensington Avenue with a building on Spadina and includes a huge parking lot between Spadina and Kensington Avenue. They have eight or ten properties on Kensington, and they want to pull down the whole east side of Kensington Avenue, right up to St. Andrews, and the beginning of that demolition has started. You can see it. They’re digging a hole.

PART III: NEIGHBOURHOOD CHARACTER

NEIGHBOURHOOD AS THEME PARK

TRAJ: Getting back the idea that the neighbourhood might be in danger of losing its natural character, one of the things that Dominique Russel and the Friends of Kensington Market greatly fear is that Kensington might turn into a kind of Disneyland.

SC: I think it’s about use. When I think of a theme park, I think of the downtown of Niagara Falls—a place that’s a theme park, but not a theme park. There is a main street that’s an amusement centre for tourists, and that’s all it is. So, if Kensington became something like that—a mall, basically for hourly tourists who walk through, buy a coffee or a Toronto tchotchke or whatever—then we would be talking about removing residents, and immigrants, and basically, creating a commercial centre of low-rise commercial interaction, around short-term, in-and-out visitors. That’s not what Kensington is.

KENSINGTON’S SENSE OF PLACE

TRAJ: Agreed. Even in a successful theme park or entertainment environment, it’s not all about how it looks, but more about how it feels. Making Kensington look like “an old village” won’t save it or even make it a successful theme park. If the immigrant population rented to Starbucks, e.g., maybe Starbucks would preserve an old-fashioned façade, but Kensington has never been about facades. So the built form is not really the issue. What matters is the life and the sense of the place. What is the “sense” of Kensington?

SC: In the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood article in the last issue of The Right Angle Journal, you talk about public space having a core value going back thousands of years, with different cultures including public space in what a settlement needs to be livable. They put in a market space, and a public square for people to congregate. But Kensington wasn’t planned out. It was an organic space. People decided it was going to be a welcome space, and generally, everyone in the city that knows about it agrees that we need it and we love it. So, the question becomes: Will the organizing forces of this society, municipal or provincial, take that into account and say, “How do we preserve that? How do we keep it as a liveable community?” Kensington has survived so far because its function has been preserved.

PART IV: MONEY MATTERS

IT'S A BUSINESS PROPOSITION

TRAJ: The issue that keeps coming up is the unavoidable conflict between money and people—the profit motive for some vs. the contentment of many.

SC: The reason the film doesn’t have a narrative ending is because there isn’t one answer to this. It’s not that the people won or the money won—it’s an ongoing heavyweight fight. At the very beginning (from 1860 to the 1920s), it was a development for suburban upper middleclass families. Then somehow, a bunch of immigrants got in, and the people won for a long time, and now the money’s winning. But we don’t know what the outcome will be, for the city or the neighbourhood. Kensington Market’s not disappearing quickly, but the culture of the city has changed, and I think people who’ve been around a long time feel it.

There have been a few new high-rise towers, focused on the University of Toronto. Some of the completed ones are tiny units for foreign students. And then you have a building that has now been built8 that was one of the first condos in the neighbourhood. It was a mix of investors, residents, and people who might want to hold it for Airbnb, or student rentals, or who knows what, but it’s a business-first proposition.

As someone who was born and grew up here, the film is a requiem for the city I’ve known. But it’s also recognizing that that spirit is still here although there’s a challenge to that spirit. It’s now money first, people second. They’re both present and the outcome is in question.

IT COMES DOWN TO THE INTENTIONS OF THE CLIENT—OWNER, DEVELOPER, BUILDER, RESIDENT OR MERCHANT

TRAJ: So, is the real question: Who are the clients, and what are their intentions?

SC: The film points out that challenge: What will the future clients’ intentions be? In high economic cycles, it’s about the growth of money, and in low cycles—recession, depression, poverty—price appreciation goes dormant. That’s when poor artists and immigrants can get access, and that’s why Kensington became what it is. The question is: In high cycles, can people’s rights be respected, and in low cycles, can we keep the economy going so the city and its neighbourhoods can survive?

As a film maker, I did dwell on this for a long time, because I feel that democracy is built on a parallel path with capitalism, with rights for human beings and rights for capital. When there’s an endless amount of space, the impact of capital is less. But when there’s no more land, and there’s too much money floating around, it starts to encroach on space for regular working people and that’s happening not just in Kensington, but all over the city. We’re the victims of our own success.

My question again is: Can the values of the city I’ve known—that we call “a people city,” that accepted millions of immigrants and gave everybody a place—be retained in a high cycle, when the space is limited, the money is international, and the profit margins are exponential? When you take a parcel of land with a three-storey building and you put on it a thousand units selling at a million bucks a piece, that’s pressure, and we’ll see what our values really are. And how do our municipal and provincial governments try to ensure balance? That’s the drama underlying the back half of the film, and it’s a conundrum faced by municipalities all over the world.

In the film, somebody talks about one property—an old Victorian poultry warehouse on St. Andrews with a little parking lot—that was being sold for $9 million. It’s now demolished. There’s another developer who’s trying to chew up a whole block on the east side of Kensington Avenue, replacing all the old Victorians, and that’s being processed.

On the other hand, there’s a brand new building on Nassau St. that replaced the old Portuguese bookstore—a one-storey low-rise—that’s shown in the film. The new two-storey building has multiple units, with a bunch of artists and offices on the upper floor and retail on the ground floor. It uses very green building materials, because the client has that value set. So, the client’s intention is the real key to how a property will be shaped.

PART V: THE TAKEAWAY

ENGAGEMENT

TRAJ: What do you hope people will take away from this film?

SC: I would like the audience to go: “Hmm, how can I learn more, or get involved, or somehow put my behaviour to voting one way or the other. Maybe I’ll come down and support the merchants, or spend more time there, or I’ll go to a public meeting, or I’ll be more cognizant of city councillors in the next election.”

STANDING UP TO AUTHORITY

TRAJ: What’s your next project?

SC: The journey of a filmmaker is not one of a lack of ideas, or imagination, or passion. There’s always a number of projects I’d love to do. It’s only a shortfall in resources. So, the question, really, is: What’s the next project I’m chasing money to do?

There’s one project I’m working on that takes place in 1958, in a little Catalan fishing village in northeastern Spain, that is under the same sort of gentrification and development pressures that Kensington faces: families that don’t want to see anything change and other families or family members that can’t wait to sell their little house so they can move to the big city and cash out. It’s a lot like the Kensington story, except that it happened over a very short time span. The details are real. The characters are fictional.

There are also a few other things I’d love to do. I’m really interested in people who stand up for their values against the strong predominant forces in their own communities and their own countries—people who have the courage to draw the line and say, “No. I’m not going to comply. I’m not going to go invisible. I believe in this and I’m willing to stand up for it.” It might be someone who doesn’t want to sell their house to a developer, or people who just stand up against folks with power—whether it’s political power, military power, financial power—who are imposing their will and agenda on a civilization or community of individuals that doesn’t have the wherewithal to oppose them. Most people stay quiet, or comply, or wait for it to pass. The people who stand up against this kind of power and do the right thing for their value set—and that’s really hard, especially if you know that there’s going to be a cost for your actions—to me, those people are heroes.

AN EXAMPLE CLOSER TO HOME: DEFENDING THE KENSINGTON UNHOUSED

TRAJ: Speaking of standing up for what you believe, there’s an excellent example in the film of someone who is part of the Kensington community who takes a stand against “the powers that be.”

SC: In an example close to home, Maggie Helwig, the priest at St. Stephen’s, [on the south boundary of Kensington Market] who appears in the film, is the leader of a moral community. When a bunch of unhoused people who just needed a place to camp out set up their tents in the courtyard of St. Stephens, the municipality, called in the police. A lot of people in the neighbourhood didn’t want these people visible, and wanted them out of the courtyard, property which is incidentally is owned by the city. Maggie Helwig said, “My moral code and the moral code of the community is that we don’t turn our backs on the poor or the unhoused, no matter how messy it gets.” And she would not kick them out.*

So, the greater community has its values, and then you have a single person trying to do their job within that community, who has to make a moral decision. Maggie Helwig’s decision has been very unpopular to some in the neighbourhood and to the city bureaucracy, and it’s possibly unpopular in the diocese because it makes it more difficult for people to access the church. People are afraid of the homeless communities, and it’s easier to not see them.

Maggie’s decision could have put her job at risk, but she made it anyway. And the forces against that decision have now been exercised to the point that every square foot of that courtyard has fences, massive concrete barriers, and security guards, sending the message: “You are not welcome,” even to walk through this courtyard.

* Maggie Helwig’s book Encampment (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2025) gives a full account of the encampment’s struggle and fills in details of the lives of its inhabitants. The book won a Toronto Book Award and has been chosen by The Globe and Mail as one of 100 Best Books of 2025.

THE AUDIENCE

TRAJ: Has the film been shown to a mixed audience? It would be a shame if it were only shown to architects.

S.C. It’s been showing for 13 months now. We had 23 screenings at the Carlton, played at the Revue, it’s played at Innes Townhall twice, and at the TIFF Lightbox. So, we’ve had about 40 public screenings in Toronto already—and that’s a long theatrical special event window—because it’s relevant to Torontonians. We hope to do more.

•••••

AFTERWORD

What exactly is a neighbourhood? It depends who you ask. To a planner, it’s a “geographically defined area . . . that serves as a social unit for its residents,” to an administrator, it’s a “statistical data unit.” To a sociologist, it’s a “social unit defined by resident interaction, shared identity, and common characteristics . . . a place where face-to-face social interactions occur.”9 To a heritage architect, it’s a collection of architectural artefacts. To the rest of us, a neighbourhood is the best way to describe where we live, or where we grew up—emotional connections tinged by a touch of nostalgia. Really, a neighbourhood is a vibe.

How is architecture implicated in the idea of neighbourhood? It would appear, not always in a good way. In the equation that Stuart Clarfield and others characterize as the struggle between people and money, architects are too often the agents of profit-seeking and growth-supporting developers, who may provide a better living environment for a few, at the possible expense of the wellbeing of many. If a neighbourhood is an intangible commodity—not a collection of forms and spaces, but an amorphous shared experience—then it is a fragile thing, easily disrupted.

If the first commitment of the architectural profession is the protection of the public interest, how can this be put to work at a neighbourhood scale? It can’t be described in construction documents, statute laws, planning regulations or, unfortunately, heritage designations. And unless the entire neighbourhood is acting as the client, neighbourhood preservation, is not within the “normal scope of architectural services.” Anyway, who finally decides what neighbourhood values are to be preserved?

Urbanization is an irresistible force. “Today, 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, a proportion that is expected to increase to 68% by 2050.”10 Increasing densities are a given, abetted by a scarce housing supply, profit motive, engineering innovation, and architectural bravado.

It makes no practical sense to allow people to stay in low-rise, low-rent buildings in an urban enclave where land prices are skyrocketing and pressure to intensify land-use is increasing. It feels like the aspirations of the city are being thwarted by a few selfish, out-of-step individuals. Gentrification, urbanization, densification and property speculation are unstoppable forces. And yet, Toronto is a city that advertises itself as a “city of neighbourhoods,” a liveable city where all are welcome, where minorities blend in and move freely and are not ghettoized as they are in some multicultural cities.11 Does it make sense culturally, morally, providently, or even promotionally, to trample on the actual neighbourhoods where Toronto’s best qualities are on constant display. If we can find millions of dollars to fund a private theme park on the waterfront, can’t we find a few dollars to preserve genuine Toronto experiences that are open and available to all?

The ultimate purpose of architecture is community. – Bryan MacKay-Lyons, The Work of MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects: Economy as Ethic. Robert McCarter. London: Thames & Hudson, 2017.

Is this a turning point, where we have to reclaim the spirit of the city? We started by saying Toronto is known as the city of neighbourhoods, but when I hear “neighbourhoods” I hear it’s a city oriented towards people, and people having a home, and they feel at home in their neighbourhood. – Stuart Clarfield

•••••

NOTES:

1. There’s No Place Like This Place, Anyplace was aired on CBC, Jan.1, 2026. You can find it at http://www.theresnoplacelikethisplace.com

2. Toronto Metropolitan University, formerly Ryerson University.

3. King of Kensington is a Canadian television sitcom that aired on CBC Television from 1975 to 1980. Al Waxman starred as Larry King, a convenience store owner in Toronto's Kensington Market who was known for helping friends and neighbours solve problems. – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al_Waxman

4. A recent newscast featured a clip of the 2025 parade. It appeared to be extremely well attended.

5. The 2025 baseball World Series was finished a few days before our discussion. And, although all Canadians (not just Torontonians) were saddened by the Toronto Blue Jays’ narrow loss to the Los Angeles Dodgers, the real takeaway—and possibly unique in professional sports history—was the exceptional spirit of camaraderie displayed by the home team.

6. A Clarification from a Planner: In Ontario, major planning decisions such as zoning changes that affect height or density, and Official Plan amendments that signal bigger policy shifts, follow a set public process, including a public meeting and a Council vote. Councillors can advocate for their communities and help bring people together, but they do not decide outcomes on their own. Staff review, city policy, and provincial rules shape what can be approved. Many decisions can also be appealed to the Ontario Land Tribunal, which is one reason councillors often work within clear limits when trying to influence a file.

7. This raises the matter of the city’s and the province’s interference with traffic flow patterns in the city—on, e.g., Eglinton (crosstown subway), Bloor West (bicycle lanes), or St. Clair (dedicated streetcar lanes)—where the assumption is that drivers and delivery trucks are only passing through the neighbourhood, not stopping in the neighbourhood, and that everyone who’s driving or walking has a predetermined destination—no wandering allowed. In all cases, automobile traffic is slow and pedestrian traffic is compromised by widely spaced crossing points that defeat strolling and dictate single-sided pedestrian experiences.

8. In the film, Stuart and his crew are offered the “first tour” of the building by the construction manager, who clearly has no knowledge about anything except the tall condo he is building and other tall buildings in the area. He is entirely unfamiliar with the adjacent neighbourhood.

9. All quotes, WIKI

10. (https://www.un.org)

11. Stuart spent three years in Boston, which according to WIKI AI, is also a “city of neighborhoods” because it is an amalgamation of several former towns, each retaining a distinct character. These neighborhoods function as enclaves due to historical, ethnic, and cultural factors, creating separate communities like the Italian-American North End, the historic Beacon Hill, and the Asian-American Chinatown. Stuart’s observation is that Boston, like many other cities with large ethnic populations, observes a more unstated but quietly understood “stay where you belong” social convention. Kensington, by way of contrast, welcomes everyone.

•••••